Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the June 21, 2018 Newsletter issued from Rancho Regenesis in the woods ±4kms west of Ek Balam Ruins; elevation ~40m (~130 ft), N20.876°, W88.170°; north-central Yucatán, MÉXICO

A LOCAL TRADITIONAL MILPA

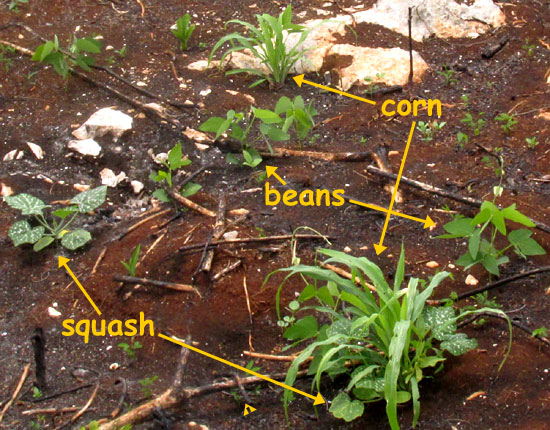

A milpa is a traditional indigenous American cornfield in which bean vines and ground-running squash are interplanted with corn, the bean plants returning nitrogen to the soil, and the squash's big leaves shadowing the soil, helping it retain moisture. Milpas, are planted in forest plots opened up by slash-and-burn clearing and are productive for three to five years or so, until weeds, insects and diseases move in. Then the plots are abandoned, the forest grows back, and eventually is slashed and burned again.

Mayan milpas are only a fraction as productive as North American cornfields using chemical fertilizers, pesticides and hybrid, often gene-manipulated seeds. However, milpa farming has sustained the Maya for thousands of years and, at least at low population densities, has proved to be sustainable.

Still, nowadays few milpas in this area produce their potential output because mostly they're planted in order to receive a government subsidy. Milpa farming is hard work, chancy, and people like to eat other things than home-cooked corn products, beans and squash. Young Maya are somewhat embarrassed to be seen working in a milpa. In this area, at the end of each milpa growing season, most milpas are so neglected that they're choked with weeds, and large numbers of raccoon-like coatis, and birds such as Yucatan Jays, take much, most or all of the produce.

However, on the road between the rancho and the village of Ek Balam there's a milpa planted he old way, with interplanted corn, beans and squash. Last month an old man could be seen there poking holes in the ground with his stick, taking seeds from his sidepouch, dropping them into his holes, and covering them with his foot. Nowadays his crop is coming up. At the top of this page you see the field and a close-up of part of it.

from the September 28, 2018 Newsletter issued from Rancho Regenesis in the woods ±4kms west of Ek Balam Ruins; elevation ~40m (~130 ft), N20.876°, W88.170°; north-central Yucatán, MÉXICO

MILPA'S CORN TASSELING OUT

Nowadays in the old man's milpa the corn is tall and tasseling out, as you can see below:

The corn is about ten feet tall (3m), taller than North American corn, but not as productive. Soon after the milpa was planted, the rainy season fizzled out and the milpa's bean vines died from lack of water. The squash and corn survived and now are doing very well.

When I pass by the milpa on early mornings, I hear rustlings in the field, and I'm pretty sure that it's birds and coatis (raccoon-like mammals) tearing into immature ears of corn, feeding. Below, you can see an example of their work:

The greenish corn grains haven't had time to develop, but already they are a little plump and juicy, and might provide a good meal to a Yucatan Jay, who is a famous corn-pilferer. These days more than ever you see coatis rushing across the highways, their tails stiffly held behind them and their bellies surely full of corn.

Because of the erratic seasons this year, most farmers in the area didn't even plant their milpas, having been unable to slash and burn their fields before the rains set in. However, the government pays their subsidies even if the crop has failed or, apparently, never planted. This year the coatis and corn-eating birds will pay special attention to the old man's milpa.

from the September 28, 2018 Newsletter issued from Rancho Regenesis in the woods ±4kms west of Ek Balam Ruins; elevation ~40m (~130 ft), N20.876°, W88.170°; north-central Yucatán, MÉXICO

MILPA SEASON ENDING

Nowadays the old man's milpa seems to have produced a decent crop. The cornstalks are brown, and the old man has walked through his cornfield breaking over every stalk so that the ear-bearing upper part hangs downward. This way, when it rains, the corn inside the ear will be better protected by the downward-pointing husks. You can see what this looks like below:

In that picture, notice the squash/pumpkin vines working their ways across the cornfield's floor. Early in the rainy season the rains failed for a couple of weeks and the beans he'd planted died, but the squash and corn survived.

issued on April 30, 2020 from Tepakán, Yucatán, MÉXICO

BURNING FOR THE MILPA

The slash-and-burn part of planting a milpa, or traditional cornfield, has reached the burning stage for a milpa adjacent to the rancho, shown below.

The burning kills insect eggs, weed seeds and disease organisms, plus it concentrates nutrients in the ashes. When rain comes, those nutrients provide a quick spurt of growth to planted seeds.

However, a good bit of the ash's nutrient value is lost when it dissolves in rainwater, seeps into cracks in the limestone, and eventually ends up in the ocean. Maybe 3-5 years after burning, a field's insects and weeds become problematic, so another part of the forest will be slashed and burned.

Studies show that where slash-and-burn is practiced with adequate resting periods between crops -- maybe 15-30 years, depending on local conditions -- the area has a higher species diversity than a mature forest typical for that area. However, here, such long resting periods, mainly needed so that organic matter can build up in soil, is unusual.