Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the June 7, 2018 Newsletter with notes from a camping trip in the mountains east of Saltillo, Coahuila, northeastern MÉXICO

MEXICAN PINYON PINE

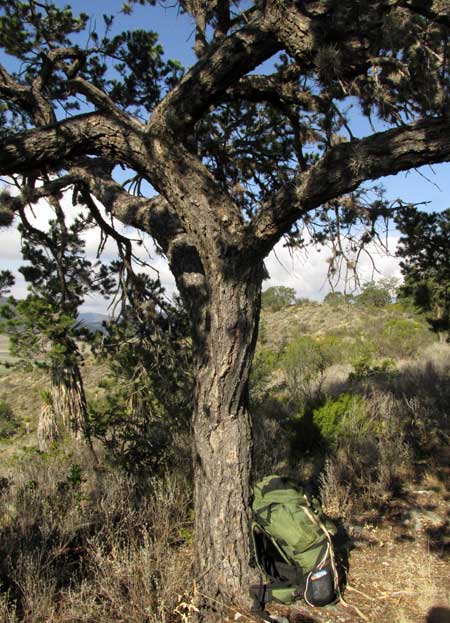

Two months ago, on April 5th, in the mountains east of Saltillo, Coahuila, I started out hiking on a valley floor, and climbed a small limestone mountain that was grassy and scrubby at its base, but forested on top. At the top, at ±7000 feet in elevation (2100m), the forest was discovered to be composed nearly entirely of widely spaced, low growing, somewhat gnarly pines and junipers. Below, you can see the wind-buffeted trunk of the pine tree beneath which I threw my tent that night, with my backpack leaning against its trunk for scale:

This tree was producing a few small cones that weren't mature yet. Below, you can see a couple among the tree's short, stiff needles:

For pine identification, important field marks are provided by cones and needles. Here we see that the cones appear to be maturing into rather small ones of a somewhat globular or spherical form. Most pine species produce their needles in clusters (there are species with only one needle per "cluster"), and the number of needles per cluster is important. This tree produced mostly three needles per cluster, but often only two, as shown below:

When a pine's needles emerge, they have at their bases, immediately above the woody knobs projecting from the stem and bearing them, there's a kind of cellophane-like sheath surrounding the needles' bases. Some species retain those sheathes while in other species the sheathes soon fall away. In the above photo you can see that in this species the sheathes are "deciduous," not "persistent."

Though the trees there weren't producing mature cones at that time, beneath the trees old cones that had lost their seeds could be found. A collection of those, with some seeds that have been nibbled on by wildlife, is shown below:

The surprising thing here is that the seeds are so large and plump, and don't bear papery "wings." In fact, the moment these seeds were noticed, it was clear that we had Pinyon Pines just like those we found atop hills in southwestern Texas's Edwards Plateau region. In Texas the species is often listed as Pinus remota, or sometimes as a variety of the Mexican Pinyon, PINUS CEMBROIDES, which is what we have here. The only difference I've noticed between the Texas plants and Mexican ones is that the Texas trees mostly had two leaves per cluster while these mostly have three.

Mexican Pinyons are so common in northern and central Mexico's highlands that in Spanish they're often called Pinos Mexicanos. They have a long history here of being used. My introduction to them was many years ago when traveling by train through northern Mexico's mountains I'd buy paper funnels filled with pinyon seeds sold by indigenous folks at stops. I and most other passengers would sit in those slowly rocking, stinky old rail cars as they rumbled up and down slopes and crossed gargantuan canyons, cracking pine-nuts and tossing the shells out the open windows.

But also the tree produces a fragrant, fast-burning firewood, a soft and not very strong but cheap and easily worked wood for construction, and resin from which waterproofing solutions and glue is made.

Often this species is planted in deforested rocky uplands, because of its resistance to drought. It does a good job protecting the soil from erosion, favors water infiltration into the soil, and as such helps reestablish aquifers.