Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the January 12, 2014 Newsletter issued from the Frio Canyon Nature Education Center in the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

SUNBURST LICHEN

One overcast morning a Texas Liveoak leaned across the trail with a small part of its deeply fissured, dark bark aglow with bright-orange lichen growing in powdery clumps, as shown below:

Other trees in the area didn't bear this lichen, but within a few feet of the above population bush stems bore many small colonies, as if they'd been splattered there by rain or carried by wind from the main group higher up on the tree, and probably they had been. Below, on one of those bush stems you can see the lichen closer up, and see that it's a "foliose" (leafy) kind with a very small, flattish body (only about 0.5mm across), instead of a crusty "crustose," or upright, shrubby "fruticose" type:

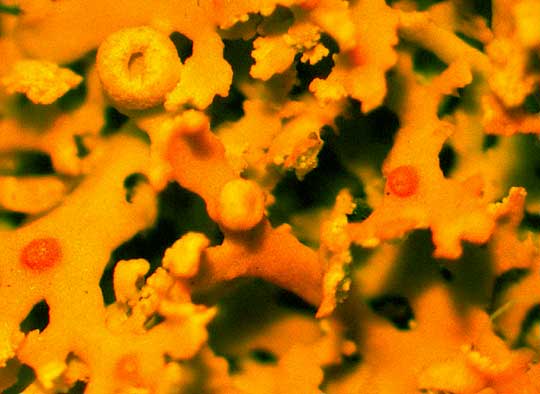

In the top, left of that picture notice the tiny, cuplike "apothecia," which are structures enabling sexual reproduction. The cups' inner surfaces are provided with a thin layer called a "hymenium," and it's where spores are formed and released. Raindrops splash into the cup, spores splash out, and new lichens form in the neighborhood. You can see the leafy lichen bodies, called thalli (singular thallus), much closer-up, below:

At the top, left of that picture, an immature, doughnut-shaped apothecium is forming. Notice that several flat lichen thalli bear brightly orange bumps in their centers. The pimples are "pycnidia," inside which special fungal hyphae produce asexual germ cells known as conidia. Lichens are composite beings consisting of cells of fungi with those of an alga and/or a cyanobacterium, so when conidia are spread to good new locations they vegetatively produce hyphae that are strictly fungal in nature. These hyphae wander around looking for the right algal and/or cyanobacterial cells with which to join to form a new lichen.

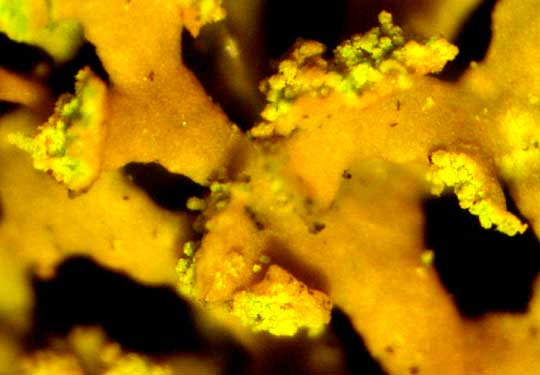

Also interesting in that picture are the tiny granules along the margins of many of the thalli. The granules are "soredia," whose job is to simply break off the main thallus and be spread elsewhere, where they'll form new lichens. Soredia are different from spores produced in the cuplike apothecium in that the soredia are asexual -- actually little pieces of the mother lichen -- while apothecium spores are sexual. Soredia differ from germ cells produced by pycnidia in that a pycnidium's germ cells produce only fungal hyphae, which must find the right alga and/or cyanobacterium before they can begin forming a new lichen. Soredia have all they need to form a new lichen. An even closer look at some soredia is shown below:

.

.

This is a kind of sunburst lichen, genus Xanthoria, one of the most conspicuous and beautiful types of all lichens, and thus a good group to know. Sunburst lichens grow in a variety of habitats, often are encountered and sometimes are abundant, and occur worldwide. Sunburst lichens are often the first kind of lichen beginning lichenologists are able to identify. About 15 sunburst lichen species are recognized for North America, so identifying them can be a challenge.

However, in 1997 Louise Lindblom at Lund University in Sweden published his "The genus Xanthoria (Fr.) Th.Fr. in North America," which is downloadable for free in PDF format at http://nhm2.uio.no/botanisk/lav/RLL/PDF/R11492.pdf.

With that publication -- especially using the distribution maps accompanying each species description -- I was able to identify our sunburst with fair certainty as the Bare-bottomed Sunburst Lichen, XANTHORIA FULVA, occurring mainly on the bark of trees, especially in the open or semi-open, though sometimes it turns up in shaded spots and on rock. It can be found throughout most of the Earth's northern temperate zone.

In this area we have another very common, brightly orange lichen species, but it's much larger and it's a shrubby "fruticose" type, unlike our leafy "foliose" sunburst. The larger orange lichen is the Slender Orange Bush Lichen, which can be compared to our sunburst at https://www.backyardnature.net/n/x/bushlich.htm.

Such brightly colored lichens traditionally were used for making dye, but the Bare-bottomed Sunburst is so small that too many colonies would have to be sacrificed for just a little yellowing, so making dye of them would be a shame.