GOLDEN DAYS

This week was long hours of bone-chilling drizzle, afternoons of cottony puff-clouds in vultury skies, warmish nights with questioning cricket chirps, and colder nights silent as dead crystal. One sensed a thousand summery traditions drawing to their ends as the annual cycle returns to its Winter Solstice.

Thursday morning after jogging I sat next to my campfire heating a pot of water with a wad of garden spearmint in it, watching what the sunlight did out in the blackberry field. That morning we had the season's fourth or fifth spotty frost, and for the second or third time a crust of thin ice glimmered in my rainwater buckets. Out in the field what little frost we had was melting and every blackberry leaf was wet, every clump of broomsedge was steaming, and the yellow-leafed Sweetgums and Hophornbeams all glowed golden in the low-slanting sunlight. The field reminded me of a child's ornate cardboard theater in which every feature was gilt, the stage, the hall, everything golden and filigreed, every random form fixed in a frozen golden glow, and all the shadows were perfectly black, black with absolutely sharp edges, a whole world of pure gold highlighted with satiny black curlicues and classic Chinese brushstrokes.

As the campfire popped and hissed and steam and smoke wafted into the naked branches of the big Pecan tree overhead, I recalled that that day the outside world was celebrating its Thanksgiving. However, I couldn't see that the day was more special than any other, so I made a point of being no more thankful than usual.

The next morning, Friday, it was even colder, the thermometer in the Waxmyrtle read 27°F, and the ice in my buckets was almost too thick to shatter with a knuckle. That morning the blackberry field was pure white and after an hour of in-slanting golden sunlight still white frost-patches lay here and there.

Toward the end of breakfast the forest and field were wet and glistening, and though no wind at all stirred, about every three seconds a leaf would simply break off a tree and float gracefully to the ground. Frost on the big Pecan tree above was melting, so for a time it sounded like a spring rain coming onto the kitchen's corrugated tin roof.

The leaves and the melt-rain cascading through dazzling sunlight, steam and woodsmoke rising up through it all, and the birds beginning to stir, and I sat there trying to keep track of every event, every change, but things simply happened too fast to keep up with.

*****

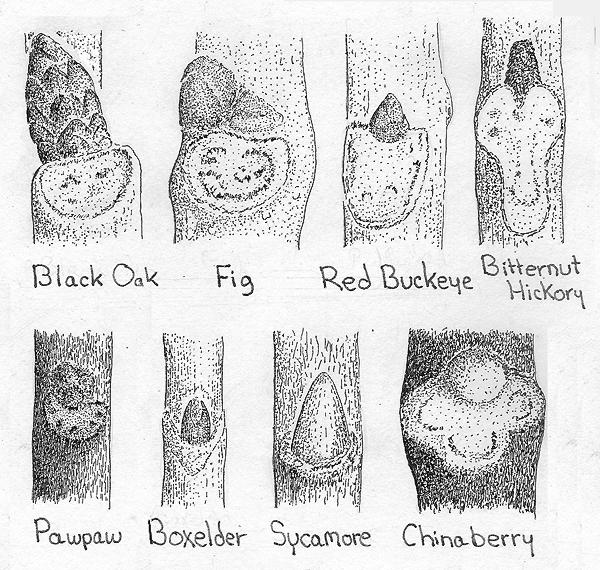

LEAFSCARS ON TWIGS

The afternoon blossoming out of that morning was splendid so I left my computer and embarked on a project I'd been saving for just such a day. I went looking for woody twigs showing a variety of leafscar patterns. Leafscars are the scars left on twigs when leaves fall off. The leafscar of each species is different from those of every other species, so you can use them to identify woody plants during their leafless winter condition. I needed these twigs to scan for my Twig Page on the Internet.

Needless to say, wandering the fields working along woods edges looking for perfect twigs was a happy time. I ate a piece of cornbread next to a pond where three large Red-eared Turtles basked in mid-day sunlight.

*****

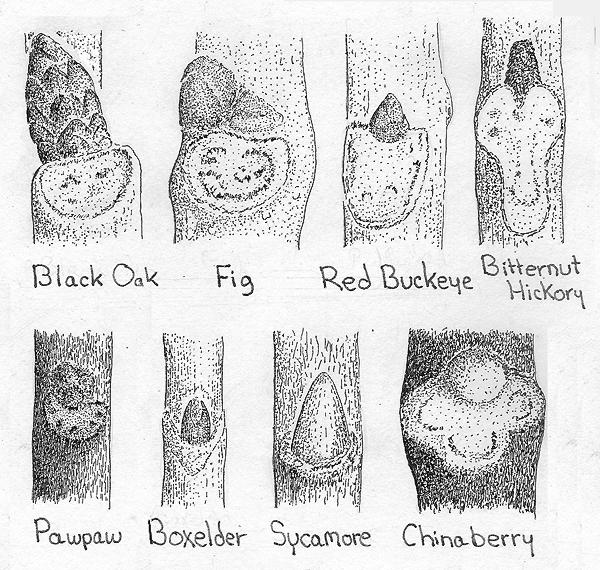

STINKY SQUID

Monday I was pulling bamboo rhizomes from the garden when in a shaded, moist spot I came upon a mushroom similar to the Stinkhorn (Dog-pecker Mushroom) I told you about in this year's January 27th Newsletter. Monday's find was about the same size and color as the January Stinkhorn but instead of having a single, dog-pecker-looking head, the head was composed of three arms arising from a common base, spreading from one another, then reuniting at their tips, and right below where the three arms connected there was a greenish blob of very stinky spore mass called gleba.

This was the Stinky Squid, Pseudocolus fusiformis. Usually it's considered to be a tropical species rarely found in the US, so this was a pretty good find.

As was the case with the fairly common January Stinkhorn, Stinky Squids arise from white, egglike structures about the size of guinea eggs. Also like the Stinkhorns, these fungi produce stinky gleba to encourage flies and other carrion-lovers to land, walk around in the stuff, then fly elsewhere, spreading spores as they go.

If I were exploring on the Moon and found this weird little beauty behind a rock, it would seem no less exotic and mysterious than it did in my garden. One looks at it marveling, just wondering at the Creator's kinky, joking streak.

*****

EASTERN HOGNOSE SNAKE

Monday morning next to our coldframe I was surprised by an Eastern Hognose Snake, Heterodon platyrhinos, sunning himself next to a bale of hay. "Surprised" is putting it mildly, since this species makes a living from looking mean. Though its coloration is extremely variable and some individuals are completely black, this one was boldly patterned like a Timber Rattler and thick like a Cottonmouth. My heart fluttered a bit before my brain took over and made a proper identification.

Making a proper identification was important because hognose snakes are among Nature's most spectacular bluffers. They are perfectly harmless critters but they look and behave as if they could chew your leg off. And the bold patterns and bright coloration of my Monday snake are only part of that bluffing.

The first thing my hognose did to increase my terror was to flatten himself. Basically hognoses are medium-size snakes, but when they spread themselves they look much more powerful than they are. When Monday's hognose saw that I wasn't running away he increased his apparent size even more by taking in an enormous amount of air and thus ballooning his body, and spreading his head into a dangerous-looking triangle, exactly like an Indian cobra. He even hissed!

This show did not prevent me from nudging my little friend with a finger, for I knew he would not bite. I have had hognoses strike at me, but they don't open their mouths. It's all pure bluff. I nudged Monday's hognose for a reason, for I wanted to see the last part of his performance.

Sure enough, after the nudge the poor snake flipped onto his back, held his mouth agape, let his tongue hang out, and just laid there, as dead-looking as a snake could possibly look. Of course, when I flipped him onto his stomach he promptly went onto his back again, and with that his repertory of responses was exhausted.

The body-flattening, air-imbibing, hood-flaring, hissing and final death scene are as inevitable with this species as its habit of eating toads and frogs -- except that tamed individuals stop going through the routines once they realize they do no good. As a kid in Kentucky when I saw my first Eastern Hognose I was sure I'd discovered a circus escapee, a real death-dealing cobra. However, when I got out my books, I learned that hognoses are a fairly common species in nearly all of the eastern US, except in the far north.

It's a wonderful snake but I fear that many have been slaughtered by humans impressed in the wrong way by their bluffing.

*****

FRESH AIR

Sometimes deep in the night I awaken to find that the air has grown stale, maybe because my nose has worked up into a corner, or the sleeping bag's hood covers my face. At the back of the trailer, my sleeping platform stands level with the windows, so when I need fresh air I can just press my nose against the window's cold screen-wire, and breathe deeply. While the rest of my body luxuriates, glowing toastily inside the bag, frigid, well oxygenated air pours into my lungs. During the seconds of that first deep breath I do believe that I feel more alive, alert, and rejuvenated than at any other moment of any day or night.

Later as I prepare breakfast, my campfire again reminds me of the power of oxygen and fresh air. The blaze may be dying out, the flames withering to a lazy smoke, but all I have to do is to blow or fan the embers, bringing more oxygen into contact with them, and then bright orange flames instantly flare up with wonderful brightness and vitality. I wonder just how many people nowadays don't even know about the magical effects of blowing or fanning a blaze?

In fact, I worry about the world being taken over by young people who have not personally experienced the stab of pleasure and flash of being vividly alive that a perfectly timed jolt of unpolluted, well oxygenated air can provide.

*****

GRAY FOX

Monday afternoon while working at the computer something caught my attention at the corner of my vision. Outside, about ten feet beyond my kitchen, there stood a Gray Fox, Urocyon cinereoargentes, sniffing at something on the forest floor. He raised his head, looked right at my door, I saw something click in his mind, and he silently and quickly slipped away and disappeared before I poked my head from the door. Gray Foxes are mostly nocturnal and very secretive, so it was something to see one so near my trailer at 3 PM. In this area they breed from December into March, so maybe romantic goings-on were afoot.

I've seen Red Foxes here before but this was my first good look at a Gray one. Actually during the last week I've been on the lookout for foxes because I've been seeing fox scats along the road -- black droppings with long tapered ends consisting of hairs of prey passing through the digestive system.

The coat of my Monday fox was thick and glossy and he gave every impression of being in full control of things, and in a good mood. His coat was strikingly two-toned -- dark gray above and dark red below.

Though Gray and Red Foxes are in entirely different genera (Reds are members of the genus Vulpes), they can look a good bit alike. The most dependable fieldmark separating them is that Red Foxes have white tail tips while Gray Fox tail-tips are dark. Red Foxes have color phases and there's a "cross phase" between the "red" and the "black" that can look like a Gray Fox's coat, but the tail tips are always the giveaway. Red Foxes also have black feet, while a Gray Fox's feet are grayish or reddish.

Gray Foxes are famous for being able to climb trees, and I'd love to see that. I've read that they shinny up tree trunks to a limb, then jump from branch to branch as they go after squirrels and birds. Their toenails are longer, sharper, and more curved than the Red Fox's, which seldom goes into trees.

The winter diets of Gray Foxes in Texas have been shown to consist of:

56% small mammals (cottontails, rats, mice

23% insects, largely grasshoppers

21% birds (doves, sparrows, blackbirds, towhees)

After glimpsing this beautiful animal I felt good the whole day.

*****

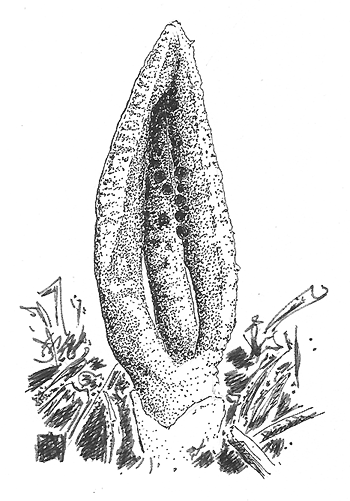

CEDAR WAXWINGS AT DAWN

Tuesday morning as I prepared my campfire breakfast the season's first flock of Cedar Waxwings glided into the top of the big Pecan tree above my camp. Even without binoculars I knew they were waxwings because their flock was so compact and the flight of each bird was so perfectly synchronized with all the others. Flocks of American Robins and Starlings are much looser -- informal you could say. But these little Cedar Waxwings were like petite soldiers positioning themselves in the Pecan with a focused, almost mechanical seriousness.

"Mechanical" is also a word coming to mind when viewing the birds with binoculars. Each buff-colored, jauntily crested adult bird wears a narrow, black mask with a neat, white border. There's a dainty dab of red at each wingtip and a dapper yellow band across each tail's tip. The prim little bird looks as if it's been concocted by a skilled German craftsman -- almost too composed, contrived, sleek and elegant to be real.

Tuesday morning about 120 waxwings adorned my big Pecan's topmost branches. At first they perched silently and unmoving about a foot apart, each bird positioned so that dawn's low-slanting sunlight struck its broad chest. Waxwings, while small, possess rounded chests, and now in the morning sunlight 120 little chests made soft, oval glowings within the big Pecan's black reticulation of naked branches.

I admired by guests a while, then returned to tending my fire. In twenty minutes I scanned them again with my binoculars and now it was a different scene, for every bird had broken into a frenzy of feather-preening and stretching. I was glad to see that they had made themselves at home.

During summers Cedar Waxwings are found in Canada and much of the northern US, as far south as the higher elevations of the southern Appalachians. In the winter they shift southward, as far south as Panama, but their northern distribution still includes part of New England and Montana.

*****

OYSTER MUSHROOMS

The other day I collected an Oyster Mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus, from the trunk of a dead Water Oak, and it was like meeting an old friend. The first wild mushroom I ever picked and ate was an Oyster Mushroom.

This species supplied my first wild mushroom meal because of three good reasons:

# It was easy to identify

# No deadly poisonous, similar-looking species existed with which it could be confused

# It was known to offer good eating

Similar mushroom species that should be avoided do exist, but they are described as tasting so bad that no one would eat them and, while unpleasant-tasting, they are not known to be poisonous. If you collect a white to cream-colored, soft-textured mushroom up to a foot across, growing on a tree trunk and, when you nibble it, it doesn't taste bad, you're OK. To be absolutely sure, Oyster Mushroom spores are white and produced so copiously that usually you can find a white "dust" of spores below the mushroom's gills -- maybe on the caps of mushrooms below them, for often this species grows in colonies.

Oyster Mushrooms derive their name from their body shape, like oyster shells, not from their taste. I find their taste to be fairly bland, but they do acquire and often improve the flavors of the good things you cook with them. The simplest and possibly the best preparation is to fry them in butter, seasoning only with salt and pepper. The one I ate the other day, however, went into the dish I usually reserve for those campfire breakfasts prepared in below-freezing weather.

That breakfast consisted of a handful of oatmeal boiled in water, with some chopped nuts added, and with two eggs dribbled into the watery mixture when it's hot enough to bubble, so that the eggs' protein forms lumps. All this is seasoned with mixed herbs, especially oregano. That morning when I snipped in an entire large Oyster Mushroom the bits of mushroom in the resulting porridge carried the mellower overtone-flavors of oregano and cooked egg yolk.

In our area Oyster Mushrooms can be found every month of the year, and sometimes you find enough growing together to pick a bushel or so. If you want to choose just one common, easy-to-identify, good-tasting mushroom to know and to eat, this is the species I'd suggest.

*****

CAMBIUM GHOSTS

If you were to cut down a tree, place a yard-long section of the trunk onto a table, and then by some magical process cause everything on the table to vanish except the trunk's cambium layer, you'd end up looking at a pale, translucent, yard-long cylinder composed of tissue-paper walls only one cell thick. The cylinder would have a diameter nearly as large as that of the vanished trunk section, for the cambium layer lies just below a tree's bark, between the bark and the wood.

If you've ever knocked a chunk of bark off a living tree and seen the smooth, slippery surface coating the inside wood, that coating was the cambium layer. The position of the cambium layer makes sense because this filmy zone comprises the only living part of the tree trunk and, as such, from it originates both bark and wood. Those cells produced by the cambium layer facing outward from the tree's center make bark, while those produced by the cambium layer facing inside make wood.

Sometimes I sit imagining what the winter woods around me might look like if only the trees' living cells were visible. Since the resulting forms would be only one cell thick, they'd be semi-transparent and probably they'd softly glow in the sunlight, ghost-like. It would be a forest of slender, pale, upward-branching cylinders rising skyward, swaying in wind so gracefully that I think that music surely would form spontaneously in the mind. This mind-music would be of a traditional Chinese kind, with tones bending, melodies flowing, all interweaving like tall stems of swaying, frost-yellowed, sunlight-glowing bamboo, accompanied by random-seeming, wood-toned percussion.

I think, to this kind of music, even I might be able to dance.

Yet, these beautiful, ghostly forms are always there, doing exactly as I describe -- just that they can only be seen with the mind, or spiritually, not with human eyes. I suppose that it's just human that I am not dancing all the time.

*****

MORNINGS ALIVE

Mornings like this one, beginning clear and frosty, then warming up fast with brilliant sunlight, are a delight. After breakfast I walk through the blackberry field as curls of dense fog rise off the broomsedge and brambles. Sunlight flooding in from the east causes the fog to glow like neon in a florescent tube. White-throated Sparrows, Towhees and Cardinals friskily flit about as if they know they inhabit a wonderland, and they mean to explore every corner.

By about 10 AM the fog is gone, the sky is deep blue and the air is perfectly fresh and pure. Now the world is young and hopeful and I stand peering into brambles and bushes as the sunlight warms my back and legs.

Though the Winter Solstice hasn't arrived yet, often bird pairs cavort in chases as if it were spring courtship time. Occasionally a White-throated Sparrow erupts with his springy Old Sam Peabody Peabody Peabody call. What a pleasure to be next to a sunny blackberry bramble when that sweet, liquid call cuts through the morning air.

*****

CROWS EATING PECANS

A few pecans remain on my trees and lately Crows have been coming to eat them. Since a crow is too heavy to light next to a pecan at the tip of a branch, it flies up to a branch-tip pecan and, for an instant suspended in mid-air, nabs its nut on the wing. Then the crow lands nearby, secures the meal between its feet, and with its pointed beak chisels it open.

The manner in which the crow positions its pecan between its feet as it chisels is interesting. This is exactly as a Blue Jay might grasp an acorn, or a Carolina Chickadee or a Tufted Titmouse might restrain a sunflower seed from a feeder. I don't think you'll see nuthatches, finches, cardinals or mockingbirds handling their food exactly like this.

That's because this food-holding technique is not at all something thought up by each bird as the occasion arises. It's an instinctual pattern of behavior shared by all members of several closely related bird families, two of which are the crow family and the chickadee/titmouse family.

Millions of years ago a now-extinct bird species, a common ancestor to both the crow and chickadee/titmouse families, was the first to use this holding-between-feet feeding strategy, and the predisposition to hold food between the feet was genetically passed on to later generations -- in the same way that today we see offspring of Sheepdogs just as predisposed to herd sheep as their parents, and descendants of toy poodles to be just as nervous and barky as their parents.

As the eons passed, our crow/chickadee ancestor's descendants dispersed over a large geographical area and its population fractured into subspecies, as the Song Sparrow is currently doing. Eventually those subspecies crystallized into many distinct species. Early during this process the family tree developed a major split down the center, just like many natural trees. On one side of the tree arose branches bearing species we now refer to as members of the Crow Family, and on the other side stood members of the family of chickadees, titmice and some others, and despite the outward dissimilarities of crows and chickadees, the unseen genes of these hundreds of species continue to register the single ancient, holding-between-the-feet evolutionary event .

So today as the crows chisel and caw and look around as crows are wont to do, I witness an evolutionary event echoing since deepest antiquity. This echo is a pure tone struck mid-course in a perfect musical score realizing itself among my Pecan trees.

*****

YELLOW MULBERRY WOOD

I'm expanding one of the gardens, a process involving digging trenches where chicken wire will be sunk into the ground so that later regular fence wire can be placed above. This may slow down the armadillos as they dig their way into the garden.

One trench passes a mulberry tree, and I've been struck by how pretty the mulberry’s roots are. Their smooth bark is a pretty reddish purple, and the wood itself, at least when freshly cut, is a rich golden hue wonderful to look at.

M. Le Page Du Pratz, whom I introduced in the August 19 Newsletter, reported how the Natchez Indians used mulberry wood as a source for yellow dye. He mentioned how different dyeing techniques resulted in cloth with varying hues of yellow and gold. I can just imagine how handsome the Natchezes' garments must have been, how their golden robes must have shone as they stood in the light of their sacred sun, on the loess bluff overlooking the Mississippi.

Really I think the mulberries of this area must be something special, possibly as a result of centuries of careful culturing by the Indians. The Natchez also wove fine garments from mulberry bark, something easy to believe if you try to break a twig from a mulberry without cleanly cutting it. Very strong fibers hold the snapped twig in place and if you keep tugging at it, it's so stringy that it tears a long gash down the limb.

*****

SIGNS OF SPRING

Wednesday morning was a frosty one, with ice in the water bucket thick enough to sting my knuckles when I broke through it for breakfast water. However, the sky was clear so, as soon as the sun came out, warm currents of moist, mellow air smelling of water melted from frosted grass began suffusing the air. But these currents of warmer air were slow to blend with lingering pools of cold night air. Even in my lungs it felt as if pockets of crystalline cold air coexisted with other pockets of balmy warm air. I had no name for a moment charmed with such frost-melt contrasts. And then I heard it:

Peter, peter, peter...

It was the Tufted Titmouse calling. The little bird recognized the feeling for which I sought a name, saying plainly that it was "spring." For, this was the titmouse's spring song. In a couple of months the woods will smile with untold numbers of clear-toned, friendly sounding peter, peter, peters.

I myself whistled peter, peter, peter and before long two other titmice replied from different parts of the woods with their own petering.

At that very instant, on that brightly sunny, crystal-clear, good-smelling Wednesday morning, with no fanfare or existential ponderings to speak of, a certain gear in my brain switched from the fall mode to the spring mode. These words I write now are typed under the influence of a springy state of mind.

Those recent fallish days of dry leaf-curls, maturing goldenrod fields, and color in tree leaves were part of a different mental landscape from the one I am inhabiting now. Now this land and I are concerned with springy, not fallish, things. We recognize the presence of the former season's residual paraphernalia but what most transfixes us now is what's sprouting and opening up, what's singing, and what's new on the face of this rejuvenating Earth.

Of course, it takes more than a single birdcall to establish a season. On Wednesday morning I looked around and saw other signs as well. Up in a Water Oak one Eastern Bluebird chased another who seemed to enjoy being chased as much as the chaser enjoyed chasing. An American Robin gulped down a white Chinaberry fruit, then emitted a nasal peep good enough for any spring morning.

If you get down on your knees and look at the ground in your garden or maybe beneath the grass in your lawn, you'll see lots of green sprouting things -- the first ramblings of chickweed, and little rosettes of Bitter Cress, and innumerable other sproutings and germinations not yet so well developed that they can be identified. In the Loblolly Field, blackberry canes are ornamented with leaf- and flower-buds so plump they look like they could burst at any moment. In places down beneath last season's brown goldenrod stems new blades of grass grow so thickly and are so green that if the goldenrod stems were gone the field in some places could pass for a suburban lawn on Easter morning.

What a surprise! I'd been so busy making stem cuttings, stratifying seeds, and fiddling with HTML code for the Internet, that I'd almost forgotten how at this time of year spring comes tiptoeing. What a pleasure that this year I know the exact moment when its presence was realized, and exactly who brought the message to me:

Peter, peter, peter...

*****

THOUGHTS FOR THE WINTER SOLSTICE

In my opinion, tomorrow, the Winter Solstice, is the official first day of spring. Winter and summer just don't exist in my manner of reckoning. In past Newsletters I've described how I conceive of Nature at this latitude as "breathing out" the blossomings and new beginnings of spring, and "breathing in" the fruitings and dying backs of fall. Today is the last day of the current annual cycle's "breathing in."

A beautiful historical symmetry is manifesting itself at this very moment in the evolution of the human spirit, and the Solstice is the appropriate time to celebrate that. Right now, in our generation, just as the anachronisms and war-inciting tendencies of our religions are becoming so troubling, there is being revealed to us through science enough to inspire humanity to a whole new level of spirituality.

Our generation is the first in human history to recognize that we inhabit a fragile dewdrop of a planet orbiting a mediocre star in an average position in a run-of-the-mill galaxy among many billions of other galaxies, in a Universe that is not only expanding, but expanding at an increasing rate. Only in 1995 did we learn for sure that other stars beside our own sun have planets orbiting them. There must be many billions of planets harboring billions of forms of life, and life-like states throughout the Universe. Before our time, no human ever had an inkling that the Creator's works could be as enormous, complex, mysterious and beautiful as now we see they really are.

Nowadays, to be "a believer," it is no longer necessary to claim to believe an ancient mythology. Now, for the first time in human history, anyone can confirm for himself or herself that humankind is enmeshed in such unending intricacy managed with such awful precision that "That which created everything is the Creator, and the Creator is good... "

*****

WARM BREEZES

Most of this week has been breezy and unseasonably warm. It was good hearing crickets chirping in the full-moon nights and Spring Peepers peeping throughout the days. Before a cold front passed through on Thursday, deep in the nights I'd awaken and just lie listening to the whoosh of wind in the trees, and a small twig tapping against the trailer.

Usually as I work at the computer I listen to classical music on Public Radio. This week they've sprinkled fairly tired Christmas carols throughout their daily offerings so I've just kept the radio off. That resulting quietness reminded me of how nice it is to hear only the wind. It was a comfort, a "Joy to the World" in wind.

Maybe a hundred years from now sociologists and psychologists will shake their heads when they recall how today we tolerate in our lives such material, social and psychological clutter -- so many inelegant distractions. They will view us as we do London slum dwellers during the time of Dickens.

In my opinion, barking dogs, traffic noise, perpetually yammering radios and TVs, jets roaring overhead... they are more than inelegant: They are actually destructive to the healthy human spirit. Clutter, whatever the kind, fogs the vision, confuses the insight, mutes the music. Interminable distractions nibble at one's senses until mental fog, emotional numbness and spiritual torpor take over.

But, nature's sounds... the sound of breezes, the trickling of water, surf at the beach, the heartbeat of a loved one... are actually therapeutic to a bruised soul. Maybe it's because these natural sounds remind us subliminally that a few solid realities do indeed exist, despite the evidence of the ever-shifting, choking clutter around us. Beyond the radio's inane noises, never-ending, majestically simple and powerful melodies stream throughout the Universe, and one sound of such a melody is that of wind deep in a warm night.

And just think: You can also walk in the fields and see the wind swirling through the broomsedge, and walk in the forests and behold that wind swaying tree limbs and sending down occasional sprays of bright leaves...

*****

LONG MOON, LOW CLOUDS

The moon has been full this week, and the path it takes across the sky nowadays has kept it visible for a long time each night. Because of the way the Earth revolves around the Sun, when the Sun's daily path keeps it low in the wintry sky, as it is now, the Moon's path keeps it especially high. Six months from now it'll be just the opposite. I've heard these full moons near the Winter Solstice called "long moons."

Earlier this week when warm breezes from the south made sitting outside at dusk especially delicious, I watched the full moon rise exactly as the sun set. Later in the night the moon lit up low, fast-moving clouds scudding northward seemingly right above the treetops. The sky was black but the clouds were pale with luminous edges. As wind streamed through the trees, the clouds were silent and ghostly, and the moon shone through the silhouetted branches of the old Pecan tree just to the east. Those warm breezes caused long strands of Spanish Moss in the Pecan Trees to sway and undulate.

What a view that was! Just compose the picture in your own head: The scraggly tree silhouette with its gesticulating moss as black as satin, the rushing, silent clouds with glowing edges, and that solid moon so bright it almost hurt the eyes to look at it, so silver, silver, with those mysterious dark blotches, and the unending sounds of wind high in the sky...

*****

THE SKY IS BLUE

Yesterday, the Winter Solstice, I took my Solstice Walk. It was sunny and breezy, and the old fields here on the plantation with broomsedge and blackberry brambles encroaching from the woods' edges were brilliant in their thousand shades of rusty-brown and gray. Framed by such muted hues, the blue sky was simply overpowering with its dark blue.

The Solstice is a time to reflect, and after a while of hiking I found myself meditating on that blue sky. Is it not significant that the sky is blue?

Imagine all the colors the sky could be, yet it is blue, a color that sets the troubled mind at peace, that implies profundity and constancy. If you feel like lying on your back in the middle of a large field and letting the mind float, what color would you want the sky to be other than blue?

It's more than that we are simply accustomed to the sky being blue. I think the sky's blueness satisfies so profoundly because we humans have evolved beneath blue skies. Not only our simian ancestors on the African plains but also the little lemur-like first mammals and the first amphibian ancestors to pull themselves onto muddy shores -- first raised their heads to see a blue sky.

So what does it say that today the blue sky pleases us so? To me it implies that the Creator was not satisfied to just make a universe that worked well and looked good. It was important that those parts of creation evolved enough to have feelings -- we birds, coyotes and humans, for example -- could potentially feel content and be at peace where we are. Could indeed feel exultant just when walking around with the eyes open.

Having the sky blue, then, is a blessing and a confirmation, and I am using those terms in a spiritual context, certainly not a religious one.

Having a blue sky on the very day I celebrate the Solstice by taking a long walk in the fields is almost too wonderful to express.

*****

THE BIRDS OF CHRISTMAS DAY

Taking a birding walk on Christmas Day is a long-established tradition with me, so this Thursday I compiled the list presented below. It was a fair, not really good, day for birding. At dawn the temperature beneath a curdled, overcast sky was 30°, but by noon it had brightened a little and the temperature had risen to 52°. Birds in the following list appear in the order in which I saw them, so you can visualize the music of the walk as it evolved. Of course I always hope that someone will take his or her own fieldguide and look up the birds as they appear in the list, just glorying in their colors, patterns, shapes, and unique features the way I do while spotting them in the field. I especially like the sparrows' browns, russets, and grays.

*** Seen during breakfast ***

1) AMERICAN CROW - ±30, raucous in pecan trees

2) BLUE JAY - ±10, gorging a Water Oak's small acorns

3) CAROLINA WREN - calling from hedgerow

4) CARDINAL - calling from hedgerow

5) MOURNING DOVE - 1 flying fast overhead

6) TUFTED TITMOUSE - 2 fussing at me from a Persimmon

7) EASTERN BOBWHITE - "chucking" in Loblolly Field

8) YELLOW-RUMPED WARBLER - 2 watching from a Sweetgum

*** Seen during walk between woods & field ***

9) TOWHEE - calling from beneath blackberry thicket

10) EASTERN BLUEBIRD - quavering song from high in sky

11) BROWN THRASHER - warning churrrr call from pines

12) WHITE-THROATED SPARROW - ± 5 eating privet fruits

13) SWAMP SPARROW - nervously chipping in Broomsedge

14) PILEATED WOODPECKER - pounding tree trunk

15) RUBY-CROWNED KINGLET - comes close to look at me

16) SONG SPARROW - several in blackberry thicket

17) RED-BELLIED WOODPECKER - high in Water Oak

18) FIELD SPARROW - preening in sun, in Broomsedge

19) MOCKINGBIRD - silently watching me from atop pine

20) AMERICAN ROBIN - ±20 in fruiting Chinese Privet

21) BLACK VULTURE - 2 flying low, down Sandy Creek

22) TURKEY VULTURE - 1 circling low over woods

23) BELTED KINGFISHER - working along Sandy Creek

24) YELLOW-BELLIED SAPSUCKER - high on Water Oak limbs

25) DOWNY WOODPECKER - high on Water Oak limbs

26) AMERICAN GOLDFINCH - eating Sweetgum-ball seeds

27) CAROLINA CHICKADEE - complaining inside hedgerow

28) AMERICAN WOODCOCK - explodes from blackberry thicket

The star of the above list is the very last one, the American Woodcock. At walk's end I was approaching camp, a bit tired and woolgathering, when suddenly this bird exploded from inside a blackberry thicket right beside me. Woodcocks are medium-sized, heavy-bodied, long-billed, and short-legged, and their furiously beating, rounded wings create a whistling, twittering sound as they fly. It's always heart-stopping when these birds explode from almost beneath you. They are mostly nocturnal, so during the day they usually sit on the ground dozing, relying on their wonderful camouflage for safety.

Woodcocks have long bills mostly used for probing the ground for earthworms. They are found around here only during the winter.

*****

CORNBREAD & TANGERINE

Seeing the woodcock was great, but I have to admit that the highlight of my Christmas Day was purely gustatory.

Earlier, friend Karen Wise had dropped by, leaving a tangerine specifically to be eaten on Christmas Day. Therefore, when I packed my bird-walk knapsack with fieldguide, notebook and cornbread, that tangerine went along.

After several hours of hiking I deposited my pleasantly weary body next to the black-watered Forest Pond. The air was still chilly but the sky was lighting up and I was downright hungry. The cornbread was as good as ever, its wholesome, baked-odor goodness intensified by the crisp, fresh air, and my hunger. While eating the cornbread I noticed that I'd forgotten the tangerine, so absent-mindedly I peeled the fruit and began eating tangerine sections along with the cornbread.

The cornbread's homey, earthy mellowness perfectly complemented the tangerine's sweet, juicy, exotic, celestialness. The simple meal struck me as perfect for that time and place. In a quiet, uncomplicated manner, the pleasure of that moment was transcendent. Imagining what the animals around me must have thought when my odor of tangerine floated to them on the morning's sun-calmed air, I just had to laugh, and finding laughter mingling with sunlight and cool, fresh air, I had to laugh some more.

Unwilling to let go of the moment, once the cornbread and tangerine were gone, I retrieved the tangerine's peelings and ate them, too, their perfumy bitterness expressing haiku-like what it was like being a hermit in chilly sunlight, hunkered next to black pond-water speckled with green duckweed, on Christmas Day.

*** END ***